Shred the Tents and Burn

the Wagons

How Tents Ruin Reenactor Credibility

by

Mark

(Silas) Tackitt

of the

44th

Tennessee Consolidated Infantry

Setting the scene, portraying the scenario and teaching our guests are important goals for reenactors. When guests enter a camp, reenactors try to convince them that they are not in the present, but in the past. A challenging question for mainstream reenactors is, "how did all these tents get here?"

"The wagons brought them," replies the reenactor.

"And where are the wagons?" asks the guest.

"Just over that hill."

Having just walked from that side of the hill and not seeing any wagons, the guests realize the answers are false and move on. When guests receive obviously false answers to one set of questions, all other questions stop because the guests believe they will continue to receive equally false answers to other questions. When guests stop talking, living history ceases and we become little more than liars wearing steamy, sweaty costumes.

The overabundance of canvas at battle reenactments ruins the historical aspect of this hobby. A typical mainstream encampment more closely resembles the tent circus found at a Society for Creative Anachronism event than an actual Civil War encampment. A reason is that too many reenactors purchase wedge and wall tents because other reenactors in their unit possess them. Another is that fresh fish need room for all the gear, furniture and worthless junk they think they need.

The number of wedge and wall tents seen at battle reenactments is far be it from realistic. Any real army would not knowingly maintain a placid, tranquil encampment within a stone's throw of the enemy. Despite this, reenactors do it all the time. An army that close to the enemy would be an army sleeping on its arms and ready to move at a moments notice. Not so with reenactors. After an event, many spend hours tearing down canvas and tossing so-called "necessary" gear into the truck and trailer.

The U.S. Regulations and orders contained within the Official Records establish clear rules for tentage and wagons while armies are on campaign. Reenactors expend much effort trying to conform to Hardee's drill manual. However, little effort is spent conforming to the regulations, orders, and practices of the armies regarding usage of tents.

1. TENT AND WAGON ALLOWANCES IN THE U.S. REGULATIONS

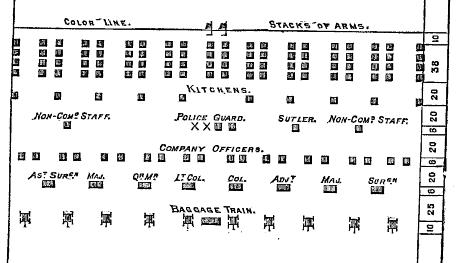

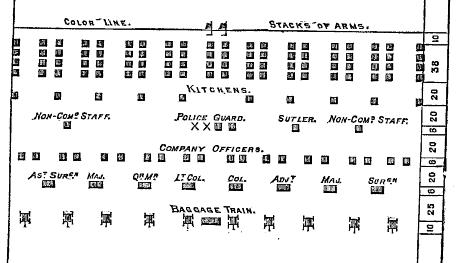

The typical encampment for a company of reenactors contains a street formed by two, parallel rows of wall, wedge or shelter tents for the enlisted men. Within each row, the tents are placed side by side, and the fronts are faced toward the interior of the street and toward the opposite row of that company's tents. At the head of the company street sits a wall tent with fly for the company commander. This arrangement resembles generally the camp specified in the U.S. Regulations.(1)

A problem with the reenactor camp is that it portrays an immobile army. For a living history event where battles or skirmishes are not expected (i.e., a garrison event), there is nothing generally wrong with a regulation encampment.(2) However, the majority of reenactments are oriented around battles. The camps are often placed adjacent to the battlefield. Unless the scenario calls for an encampment to be overrun by the enemy (think Shiloh or Cedar Creek), a regulation encampment should not be placed adjacent to a battlefield or within site of the enemy's camp.

Another problem is that reenactors refuse to share tentage with other reenactors. Typically, one tent houses one reenactor. Even when garrisoned, Civil War soldiers shared tents with other soldiers. On campaign, only the highest general may have actually bunked by himself. Not so the men in the field. According to the regulations, "every fifteen foot or thirteen mounted men," should be housed in one wall tent.(3) According to Col. Henry Lee Scott, that was too many soldiers in one space. He suggested, "A tent, generally calculated for 16 men, ought never to contain more than 12 or 13 infantry, and 8 or 10 cavalry."(4)

A final problem is that the regulations contemplate that units will sometimes encamp without tents: "In infantry, the fires are made ... on the ground that would be occupied by the tents in camp. The companies are placed around them, and if possible construct shelters."(5) When was the last time you saw a reenactment without ANY tents? They occur, but such events are few and far between.

Campaign regulations are not as draconian or masochistic as most mainstreamers believe. The U.S. Regulations state:

43. In an active campaign, troops must be prepared to bivouac on the march, the allowance of tents being limited as follows: [ ] For the Colonel, Field, and Staff of a full regiment, three wall tents; and for every other commissioned officer, one shelter tent each. For every two non-commissioned officers, soldiers, officers servants, and other camp followers, one shelter tent. One hospital tent will be allowed office purposes at Corps headquarters, and one wall tent at those of a Division or a Brigade. All tents beyond this allowance will be left at the Depot.(6)

This means that only field officers plus their staff are entitled to reside in wall tents. "Shelter tents only are allowed only to company officers and men[.]"(7) Company officers received a complete shelter tent (meaning two shelter halves), and each enlisted man received one shelter half which was approximately five and one half feet square.(8) Although small, a shelter half was extremely useful. A circular from U.S. Quartermaster General M.C. Meigs gives a glowing recommendation for the uses of shelter halves:

The shelter-tent is of much use to the soldiers.

1. It serves, buttoned up, as a bag, in which the man sleeps, under the large tent, or anywhere.

2. It serves as a bag to collect provisions and forage.

3. The men, buttoning them together, make of them tents or galleries, under which they are protected from the cold and rain. The more men unite, the better the tent, but eight men together [!] can make an excellent tent.(9)

In an effort to decrease the reliance upon regimental baggage trains, the Regulations stated the allowable baggage per person:

44. Officer's baggage will be limited to blankets, one small valise or carpet bag, and a moderate mess kit. The men will carry their own blankets and shelter tents, and reduce the contents of their knapsacks as much as possible.(10)

The regulations contemplated that soldiers on campaign would continue to rely upon the wagons to carry the tentage, cooking utensils, and officers' baggage.(11) A "full" infantry regiment, meaning ten companies of one hundred men each, was entitled to six wagons. "In no case will this allowance be exceeded, but always proportionately reduced according to the number of officers and men actually present."(12) Remember this quote as it has subsequent ramifications in this article.

The next paragraph detailed what items were allowed to be carried in the six regimental wagons:

42. The wagons allowed to a regiment, battery or squadron, must carry nothing but the forage for the teams, cooking utensils, and rations for the troops, hospital stores, and officers baggage. One wagon to each regiment will transport exclusively hospital supplies, under the direction of the regimental surgeon; the one for Regimental headquarters will carry the grain for the officers horses; and the three allowed for each battery or squadron will be at least half loaded with grain for their own teams. Stores in bulk and ammunition will be carried in the regular or special supply trains.(13)

With two wagons devoted to hospital supplies and horse feed, a regiment of one thousand possessed only four wagons devoted exclusively to the men. A regiment of a thousand men existed only a matter of weeks before disease, desertion, and death took their toll. In a matter of months, a thousand man regiment could be whittled down to five hundred men. A veteran regiment of two hundred and fifty was not unusual.

Here is where that above quotation applies. A reduction in men also meant a reduction in wagons devoted to the men.(14) The wagons devoted exclusively to the men in a regiment of five hundred men would be reduced from four wagons to two. A veteran regiment of two hundred fifty men would be reduced to one wagon. Imagine trying to place the tents and gear of a typical, mainstream reenacting company of twenty men into one period wagon. Most reenacting companies would need more than an actual regiment's worth of wagons to haul all the gear believed necessary for a weekend of reenacting. Then think about the staggering number of wagons it would take to transport ten companies of mainstream reenactors.

2. THE PRACTICES OF THE ARMIES

Generally, Federal and Confederate armies on the march conformed to the regulations noted above. Through 1862, the regulations were closely followed. Beginning in 1863, Confederates went to lesser and lesser allowances for reasons of speed and lack of horses. By 1865, Federal campaign units had learned to travel with little impendia.

A. 1861-62: a Hard Time on the Horses

In the first two summers of the war, Federals exceeded or followed the regulations while Confederates followed or abided with less than prescribed by the regulations.

General McClellan had the slows for a reason: his army transported far more than it needed. Encumbered by his army's impediments (as well as his lack of nerve), Little Mac crawled up the Virginia Peninsular. Believing he had stretched his supply lines too thin, he dropped his impediments and retreated quickly to the security of his gun boats on the James. After catching his breath at Harrison's Landing, he wrote orders which restated the U.S. Regulations listed previously.(15) As usual, Little Mac's timing was poor. He should have issued the orders before he proceeded up the Peninsular, not after his army had dropped, destroyed or discarded much of its property as it fled to perceived safety.

During Jackson's Valley Campaign three months before Little Mac's infamous "change of base," General Ewell wrote one of the more famous lines of the war:

"The road to glory cannot be followed with much baggage. Your command might be advised that if overloaded with articles not indispensably necessary their progress in the march will be impossible...."(16)

Gen. Ewell wrote that his troops transported, "...only necessary cooking utensils in bags (not chests), axes, picks, spades, and tent-flies, and the lawful amount of officers baggage and subsistence stores (80 to 100 pounds), horseshoes, & c."(17) Gen. Ewell also wrote:

You cannot bring tents; [bring] tent-flies without poles, or tents cut down to that size, and only as few as are indispensable. No mess-chests, trunks, &c. It is better to leave these things where you are than throw them away after starting. We can get along without anything but food and ammunition.(18)

At this stage of the war, Gen. Ewell had yet to participate directly in any large scale battles. However, his veteran attitude derived from many years of practical experience in the Old Army chasing Native Americans on the Southwestern frontier. Many a Confederate was thankful that Little Mac spent his years in the Old Army studying the art of war rather than practicing it like Gen. Ewell.

When General Robert E. Lee took command of what would he rename the Army of Northern Virginia, he sought to procure tentage for his army. In a request he penned to the quartermaster general, he stated:

This army has with it in the field little or no protection from weather. Tents seem to have been abandoned, and the men cover themselves by means of their blankets and other contrivances. The shelter-tent seems to be preferred by them, and I have thought that something could be manufactured out of the tents now on hand better than what they have in use. A simple fly, or cloth of that shape, would answer the purpose.(19)

When sending reinforcements to assist General Kirby Smith in August, 1862, a Confederate division commander in Knoxville advised two of his colonels, "you will see that [your regiments are] not encumbered with any superfluous or unnecessary baggage, the soldier taking only his proper kit. But 5 wagons will be allowed to a regiment and not more than one tent to each company."(20) A reason for the directive was that the army was unable to hire a sufficient number of teamsters for the "large number of wagons now employed in the supply trains...."(21) The commander's five wagon allowance was sufficient for a force of 750 men. As both units contained less than 750 men, the allowance of five wagons per regiment was more generous than that allowed by the regulations.

In response to orders from General U.S. Grant in the first phase of the Vicksburg Campaign in late 1862, the three divisions composing the "Left Wing"of Gen. Grant's Department of the Tennessee were ordered to have, "three days' rations in haversacks, three days' in wagons, and 100 [rounds] of ammunition per man. Not more than one tent per company will be taken; no other baggage."(22) The order does not state if the solitary tent means a wall tent or wedge tent.

The effect of Gen. Grant's order is great as this corps contained thirty one regiments with a likely 310 companies. By allowing each company to possess one tent rather than no tents as contemplated in the Regulations, this corps was forced to add many more wagons to the train solely for the purpose of hauling the extra tentage.(23)

B. 1863: The Beginning of the Great Reduction

As the war entered 1863, the allowances for tents and wagons decreased. On the Federal side, the reason was increased speed which occurred from transporting lesser gear. On the Confederate side, the reasons were dwindling supplies and ability to move the supplies. A trend within Confederate armies was the substitution of tent flies for wall and shelter tents.

After the infamous Mud March, Federal officers sought a way to advance the army without the large trains which had slowed, then stopped Burnside. General Meig's "Flying Column" became the answer. The goal was for the army to advance by "do[ing] away with all wagons."(24) Essentially, the advance force would carry eight days rations plus extra ammunition. On the day following the advance, wagons and additional troops would be sent forward to "revictual the column." The column would, "march forward, overthrow the enemy, take his works, and establish [itself]." The column would repeat the procedure on following days "and keep always advancing."(25)

A special board was formed on 7 March 1863 to "consider and experiment upon the best method" of implementing the Flying Column.(26) The board's mission was to "view the marching of troops without incumbrance of extra clothing or shelter-tents...." The board considered the 1½ pounds that each shelter half weighed and excluded it due to the weight.(27)

General Hooker's army implemented the Flying Column concept for the Chancellorsville campaign. Although the Federals lost the battle, the quick movements by the Army of the Potomac were extremely successful. In response to an inquiry from the army's Gen. Meigs about how well the army performed when it implemented his column concept, General Dan Butterfield wrote:

The movements incident to General Hooker's operations could not have been accomplished if the troops had been compelled to march with three days' rations only, and carrying the balance on wheels. [ ] Most of the officers speak very favorably of the facility of movement of heavy columns divested of huge trains.(28)

In response to the same inquiry from Meigs, Chief Quartermaster Rufus Ingalls supplied reports from each of the corps quartermasters in the Army of the Potomac. Despite the Board's finding against the use of shelter halves, six of the seven corps quartermasters reported that the soldiers in his corps carried shelter halves.(29) It seems that the extra weight of 1½ pounds of canvas did not overburden the soldiers. However, several of the corps quartermasters stated that soldiers were overburdened from carrying a blanket and great coat instead of one or the other as contemplated by the board and by marching orders for the campaign.

Gen. Meigs believed that Hooker's use of his column concept had revolutionized the war. And right he was. On the Confederate side, changes were also being made but for different reasons.

Lacking adequate forage and animals in April, 1863, J.E.B. Stuart cut the burden on his animals by decreasing his command's impediments. Stuart authorized the possession of wall tents to only his division and brigade commanders. That was one wall tent per headquarters, not three as allowed in the regulations. Brigade and regimental field officers received tent flies as a substitute for their former wall tent allowance:

One tent fly for every 4 commissioned officers, and one for every 10 non- commissioned officers and privates. [ ] Each officer will be allowed a small hand-trunk or valise, and enlisted men will carry one blanket and a change of underclothes on their horses. The wagons allowed to regiments and brigades must be used solely for the transportation of supplies, tents, flies, and cooking utensils. No other baggage than that specified will be allowed under any circumstances.(30)

That same April, General Hardee planned a movement for his Confederate corps stationed in Tennessee. In his marching orders, he noted, "The allowance of tents will be one wall-tent for every 15 men."(31) Two days later, he countermanded the generous tent allowance for his corps after learning his orders contradicted those of the Army of Tennessee:

The camp equipage allowed by Generals Orders, No. 78 dated Headquarters Army of Tennessee, April 13, 1863, only will be carried, to wit: One tent to each regiment for medical department; one tent to each regimental headquarters; two tents to each brigade headquarters; two tents to each division headquarters; six tent-flies for every 100 men.(32) (Emphasis added.)

Merely because orders were issued for the efficient distribution of wagons, did not mean that the wagons for a regiment, brigade or even a division followed the unit closely. A dispatch from General Thomas J. Wood of Rosecrans' army just before Chickamauga illustrates this: "I should be most happy to hear something of my baggage and supply trains; how they are getting along. Not an officer in the division has a tent or baggage."(33)

Having wagons did not help General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee. After battling outside Murfreesboro in January, he explained to Richmond that,

...our forces had been in line of battle for five days and nights, with but little rest, having no reserves; their baggage and tents had been loaded and the wagons were 4 miles off. [T]he weather had been severe from cold and almost constant rain, and we had no change of clothing, and in many places could not have fires. The necessary consequence was great exhaustion of officers and men....(34)

Bragg's men possessed wagons, but were generally unable to receive anything from them for days due to the distance. The conditions must have been miserable.

C. 1864: Active Campaigns Spur Reductions in Gear

The less an army carries, the more active it can be. Lessons learned in earlier years about the merits of less baggage become the rule rather than the exception for the remainder of the war.

During January when General Wm. T. Sherman prepared for his raid on Meridian, Mississippi, he ordered that:

III. The command designated for the field will be lightly equipped -- no tents or luggage save what is carried by the officers, men, and horses. Wagons must be reserved for food and ammunition. [ ]

V. The expedition is one of celerity, and all things must tend to that. Corps commanders and staff officers will see that our movements are not embarrassed by wheeled vehicles improperly loaded. Not a tent will be carried, from the commander-in-chief down.(35)

When General Grant received command of all Union forces, he sought to make them work in unison to prevent Confederate forces from rushing reserves from inactive areas to active areas. Consequently, the Spring of 1864 witnessed a dearth of campaign orders.

In mid-April, Federal General McPherson issued an ambitious order for his Army of the Tennessee. He wrote:

First. Each regiment, battery, or detachment will be allowed two wagons and no more; one for the cooking utensils of the men, the other for the baggage and mess of the officers. [ ]

Fifth. Not a tent will be taken with the army, and officers will govern themselves accordingly.

All surplus baggage must be thrown out and disposed of at once, and the army placed in a condition to move.(36)

Contemporaneously with McPherson's orders, General Meade issued a more standard set of orders to his Army of the Potomac. His orders mirrored those of the U.S. Regulations:

For each regiment of infantry or cavalry and battalion of heavy artillery, for baggage, camp equipage, & c., not to exceed 2 wagons, 3 wall-tents, for field and staff, 1 shelter-tent for every other commissioned officer, and 1 shelter-tent for every 2 non-commissioned officers, soldiers, servants, and camp followers.(37)

Two weeks before Gen. Meade issued the above orders, Gen. Lee prepared his Army of Northern Virginia for the eventual movement of Meade's army. Under Lee's orders, a regiment of 375 men was entitled to three, four-horse wagons of four horses each. One of the wagons was devoted to the men's cooking utensils while the other two were for officers and staff. Each field officer was permitted to bring 50 pounds of personal baggage. All other officers were allowed 30 pounds of personal baggage.(38) No officer trunks were allowed in the wagons. This three wagon allowance excluded allowances for a unit's ordnance. And what of the men's personal baggage? Gen. Lee's order was explicit: "The men will carry their baggage on their persons."(39)

The tent allowance for the Army of Northern Virginia was one wall tent and fly to each regimental commander, and "Shelter tents will be issued to the troops as far is practicable."(40) Rarely were shelter tents issued. A South Carolina soldier in A.P. Hill's Corps wrote that the source for enlisted shelters was their officer's tents:

Orders to prepare to march arrived in Hill's winter camps around 11:00 a.m. [ ] Simultaneously, the enlisted men, according to previous instructions, pulled down their officers' tents and cut them apart to distribute to the rank and file for shelters.(41)

Action in Western Louisiana was far less volatile than in the Eastern or Western theaters. Accordingly, the tent allowances for Union troops were far more liberal than in Meade's Army of the Potomac. Here, each company was allowed to possess, "one A-tent for the company officers; to each regiment, two wall-tents; [ ] A valise or carpet-bag will be allowed to be carried for the clothing of each officer; also a mess-chest of small size for each officer's mess."(42) No tent allowance is mentioned for the men, but probably it is the standard one shelter half for each individual soldier.

One of the more ambitious plans from a Union general came from General David Hunter as he prepared his army for a march up the Shenandoah Valley in May, 1864. In his General Orders, he wrote what should be carried and why:

It is if the utmost importance that this army be placed in a situation for immediate efficiency. We are contending against an enemy who is in earnest, and if we expect success, we too must be in earnest. We must be willing to make sacrifices, willing to suffer for a short time, that a glorious result may crown our efforts. The country is expecting every man to do his duty, and this done an ever kind Providence will certainly grant us complete success.

I. Every tent will be immediately turned in for transportation to Martinsburg, and all baggage not expressly allowed by this order will be at once sent to the rear. There will be but one wagon allowed to each regiment and this will only be used to transport spare ammunition, camp kettles, tools, and mess pans. Every wagon will have eight picked horses or mules, two drivers, and two saddles. [ ]

II. For the expedition on hand, the clothes each soldier has on his back, with one pair of extra shoes and socks, are amply sufficient. Everything else in shape of clothing will be packed to-day and sent to the rear. Each knapsack will contain 100 rounds of ammunition, carefully packed; 4 pounds of hard bread, to last eight days; 10 rations of coffee, sugar, and salt, 1 pair of shoes and socks, and nothing else.(43)

This Jackson-esque order bore fruit for Hunter's army as it marched up the Valley with little opposition. Eventually the toll of the orders limited the fighting capabilities of his army, and it was forced to retrace its steps down the Valley. An additional reason why it retreated was Jubal Early's Second Corps caught, engaged and pushed Hunter from the Valley.

Early's marching orders at the commencement of his pursuit are similar to those initially issued by his adversary:

IV. The following reduction of transportation in this army is ordered, and will be made immediately. [ ] to every 500 men will be allowed one 4-horse wagon for cooking utensils of officers and men. Regimental and company officers must carry for themselves such underclothing as they need for the present expedition, and the remainder of their baggage with the regimental baggage wagons will be stored at such place as the chief quartermaster may direct until they can be brought to the command.(44)

The greatest concentration of reenactor wall-tents can be found in the camps of cavalry and artillery. These reenactors often justify their tentage on their perceived need to store their tack or cannon implements. Old Jube had something to say to them as well, "The above applies equally to the battalions of artillery as to the regiments of infantry and cavalry."(45) That he specifically targeted these two branches of service shows that period cavalry and artillery tended to transport too much gear just as their reenacting counterparts do today.

Throughout the general orders, an exception had been made for the top ranking officers at brigade and division levels. These generals and their staffs were allowed one to three wall tents per headquarters. An exception to this rule occurred in General Sherman's army. In January, 1865, orders were issued to the Army of the Tennessee as it prepared to move northward through South Carolina. General O.O. Howard wrote these marching orders to his staff.

I. The headquarters for the field will be stripped of every article not strictly necessary in the field. Officers' baggage and office furniture will be reduced as much as possible, and so arranged as to occupy but little room. Flys will be used for shelter, one tent for office purposes only being allowed.(46)

Gen. Howard commanded two army corps at that time, Logan's Fifteenth Corps and Blair's Seventeenth Corps. The order was likely echoed to these generals and those below them as it is unlikely Gen. Howard would have ordered himself and his staff to abide with less while allowing the staffs of junior officers at the corps, division, brigade, and regimental levels to possess more.

3. MAXIMUM TENT ALLOWANCES FOR CAMPAIGNERS

Based upon the records and practices of the armies, a reenacting campaign unit need not go without any tentage, nor must it rely exclusively upon what is carried by the soldiers themselves. However, each soldier should be self-supporting. This means he must possess his own food, shelter, and utensils. The regulations state which utensils should be taken: "On marches and in the field, the only mess furniture of the soldier will be one tin plate, one tin cup, one knife, fork, and spoon to each man, to be carried by himself on the march."(47)

Regarding tentage, the general rule is that every reenactor should carry one shelter half. Two soldiers can make the standard dog tent. At times, three soldiers combined their shelter halves to make a structure with an enclosed end.(48) A shelter for six made from shelter halves was contemplated at the onset of the war.(49) If the soldiers did it for weeks or months at a time, then reenactors should be able to do it for a couple days. An exception to the use of shelters applies to Western Theater Confederates and Eastern Theater Confederate cavalrymen as they utilized tent flies, not shelters. Another exception concerns the event scenario. If it is based upon a particular campaign, battle or skirmish, then the participants should take the effort to read about the event, learn what soldiers did during the event, and then recreate what the soldiers did.

As an alternative to shelter halves, most units can utilize one fly per every eight to ten men. A fly is really a wagon item, but it could be carried to an event site by securing it to a pole and having two men carry the pole on their shoulders. The burden of carrying the fly can be rotated within the unit. Once at a camp site, the fly may be set by supporting it on firewood placed on end and inside the fly at distances sufficient to keep it off the ground. A period drawing of a low slung fly is found in the Battles and Leaders series.(50) The tent fly method is a practical alternative for shelter at dry, hot events where shade is necessary during the day or at rainy events when any coverage at any time is welcome relief. But where does one hide the ice chest? At home where it belongs.

4. CONCLUSION

At the close of the 19th Century, a photographer sought to photograph Native Americans to preserve a record of their identity for posterity. His excellent photos are well known and well distributed to this day. Unfortunately, the photographer did not always allow his subjects to wear their own regalia. He brought a trunk with various feathered head dresses and other items for them to wear. He explained to them that they must wear the items because Whites expected real Indians to wear the feathered regalia and would not recognize them as Indians without it. Reluctantly, they consented and became the original farbs - they assumed personas far be it from their own personas.

In justifying all the reenactment tentage, the argument most often raised by mainstreamers is that our guests want to see the tent cities. The argument is a cop-out. All that canvas exists for the benefit of the tent dwellers, not the tent viewers. Reenactors should strive to accurately portray the encampments as they really were by conforming to the regulations, orders and practices of Civil War soldiers, not to the pretended wants of our guests.

A reenacting campaign unit need not go without all tentage. The regulations, orders, and practices of the armies indicate that Civil War soldiers did possess canvas. Nothing is wrong about a reenacting company which goes without canvas because soldiers on both sides certainly went completely without canvas at varying times. However, nothing is right about individual reenactors residing by themselves in wall, wedge, or shelter tents in close proximity to the enemy.

A significant decrease in the amount of canvas presently used by reenactors would create more realistic and authentic camps. Less canvas decreases impediments because there is less space to store that useless junk. Also, less canvas increases opportunities for living history because our guests want to know how soldiers really lived. Instead of telling lies about how all the tents got there, campaigners can speak truthfully about how soldiers traveled, lived and persevered during four rough years of war.

So, improve your company's persona by shredding the tents and burning the wagons.

Mark (Silas) Tackitt is a campaigner in the Pacific Northwest whose reenacting pages are linked from 44Tennessee.tripod.com.

1. U.S. Regulations (1861), page 77, plate 1. "Each company has its tents in two files, facing on a street perpendicular to the color line. The width of the street depends on the front of the camp, but should not exceed 5 paces. The interval between the ranks of tents is 2 paces; between the files of tents of adjacent companies, 2 paces; between regiments, 22 paces." U.S. Regulations, para. 515. "The company officers are in rear of their respective companies; the Captains on the right." U.S. Regulations, para., 517. The Colonel and Lieutenant-Colonel are near the centre of the line of field and staff...." U.S. Regulations, para. 518. This same illustration of how a regiment should be formed can also be found in Col Henry Lee Scott, Military Dictionary: comprising technical definitions; information on raising and keeping troops; actual service, including makeshifts and improved material; and law, government, regulation, and administration relating to land forces, (D. Van Nostrand, New York, 1861) in figure 99 at page 143.

2. Col. Scott recognized that accidents of terrain may not allow the formation of a regulation camp:

"The shelters or huts are aligned, as well as the nature of the ground admits, from one extremity of the camp to the other, and arranged by companies in streets, perpendicular to the front."

Scott, Military Dictionary, page 133 (emphasis added).

3. Scott, Military Dictionary, pp. 638-39 (utensils).

4. Scott, Military Dictionary, pp. 134 (camps)

5. U.S. Regulations, para. 547.

6. Paragraph 43, U.S. Army Regulations (1861) as amended in Appendix B (25 June 1863). (Hereinafter, Appendix B.) The same regulations are also found in orders issued by the U.S. War Department in 1862 as General Orders, No. 160 from General Halleck's War Department dated 18 October 1862. Series III, Vol. 2, p. 671. These general orders were included in an appendix to oral testimony given during General McDowell's Court of Inquiry following the debacle of Second Bull Run.

7. Appendix B, para. 10.

8. Under General Orders No. 60, Quartermaster General's Office, December 12, 1864, corrected, February 1, 1865, the length as measured along the foot or top is five feet, six inches. The width as measured along the seam is five feet, five inches.

9. Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 491; Quartermaster-General's Office, Washington City, January 2, 1862.

10. Appendix B, para. 44.

11. Scott, Military Dictionary , pp. 638-39 (utensils):

... to every 15 foot and 13 mounted men, ... in the field, two spades, two axes, two pickaxes, two hatchets, two camp kettles, and five mess pans. Bed sacks are provided for troops in garrison, and iron pots may be furnished to them instead of camp kettles. [ ] The prescribed cooking utensils are evidently not adapted to field service. The soldier is made too dependent on a baggage train.

12. Appendix B, para. 41.

13. Appendix B, para. 42.

14. On 10 March 1863, the wagon allowance for the Army of the Potomac was marginally increased. See, Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 562-63. An infantry regiment of 700 to 1000 present was allowed six total wagons, four devoted to the men. A regiment of 500 to 700 men was allowed five wagons, three for the men. A regiment with less than 500 men was allowed four wagons, two to the men. Tent allowances remained the same in the new order. The new wagon allowance was superceded by the allowance established by Appendix B of the U.S. Regulations three months later.

15. General Orders, No. 153. Hdqrs, Army of the Potomac, Camp near Harrison's Landing, Va., Aug. 10, '62; Vol. 11 (Pt. III) p. 366.

16. Orders from Major-General R.S. Ewell to General L. O'B. Branch; Headquarters Third Division, May 14, 1862; Vol. 12 (Pt. III) p. 890. The items mentioned within the brackets are as written in the original.

17. Id.

18. Orders from Major-General R.S. Ewell to General L. O'B. Branch; Headquarters Third Division, May 15, 1862; Vol. 12 (Pt. III) p. 891-92.

19. Gen. R.E. Lee to Col. A. C. MYERS, Quartermaster-General, dated 10 June 1862; Vol. 11 (Pt. III) 585;

20. Headquartrs Department of East Tennessee, Knoxville, Tenn., August 25, 1862, Vol. 16 (Pt II) 775-79.

21. Vol. 16 (Pt. II) 773.

22. Special Orders, No. 7 Headquarters District of Corinth, Third Div., Dept. of the Tennessee, Corinth, November 1, 1862; Vol. 17 (Pt. II) 313; See also, Organization of Troops in the Department of the Tennessee, Vol. 17 (Pt. II) 339-40. The aggregate infantry present for duty on 10 November 1862 was 10,805 aggregate men and officers present for duty. With thirty one regiments, the average size of each regiment would be approximately 350 men. If each regiment had ten companies, that is thirty five officers and men per company.

23. General Orders, No. 160 from General Halleck's War Department dated 18 October 1862; Series III, Vol. 2, p. 671.

24. See, Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 490.

25. Id.

26. See, Special Orders, No. 65. Headquarters Army of the Potomac, Camp near Falmouth, VA., March 7, 1863; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 487. Three days later, Gen. Rufus Ingalls increased the regimental wagon allowance (see, Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 562-63) which was superceded by Appendix B of the U.S. Regulations three months later.

27. Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 488-89.

28. Chief of Staff, Gen. Daniel Butterfield to Quartermaster General M.C. Meigs dated 13 May 1863; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 486-87.

29. Report from Chief Quartermaster General Rufus Ingalls to Quartermaster General Meigs dated 29 May 1864; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 545. Report from Lt. Col., J.J. Dana, Chief Quartermaster, First Corps to Gen. Ingalls dated 24 May 1864; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 547. Report from Lt. Col., R.N. Bachelder, Chief Quartermaster, Second Corps to Gen. Ingalls dated 23 May 1864; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 549. The report of Capt. Jas. F. Rusling, acting Chief Quartermaster for the Third Corps failed to mention whether the corps used shelter halves; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 548. Report from Capt. J.F. Caslow, acting Chief Quartermaster for the Fifth Corps to Gen. Ingalls dated 25 May 1864; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 552. Report from Lt. Col., C.W. Tolles, Chief Quartermaster, Sixth Corps to Gen. Ingalls dated 23 May 1864; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 554. Report from Lt. Col., W.G. LeDuc, Chief Quartermaster, Eleventh Corps to Gen. Ingalls dated 24 May 1864; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 555. Report from Lt. Col., W.R. Hopkins, Chief Quartermaster, Twelfth Corps to Gen. Ingalls dated 23 May 1864; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 559.

30. General Orders, No. 13: Headquarters Cavalry Division, April 23, 1863.; Vol. 25 (Pt. II) 859-60.

31. Special Orders, No. 92 [91]. Hdqrs. Hardee's Corps, Army of Tenn., Tullahoma, April 20 [21?], 1863; Vol. 23 (Pt. II) 779.

32. Special Orders, No. 93. Hdqrs. Hardee's Corps, Army of Tenn., Tullahoma, April 22, 1863; Vol. 23 (Pt. II) 783.

33. Correspondence between Brig. Gen. Th. J. Wood and Capt. P.P. Oldershaw, Asst. Adj. Gen. 21st Corps, dated 3 Sept 63; Vol. 30 (Pt III) 981-82.

34. Report from General Braxton Bragg commanding the Army of Tennessee to Gen. S. Cooper, Adjutant [and Inspector] General, Richmond, Va., dated 23 February 1863 at Tullahoma, Tenn.; Vol. 20 (Pt. I) 668-69.

35. Special Field Orders, No. 11. Hdqrs, Dept. of the Tennessee, Memphis, Tenn., January 27, 1864; Vol. 32 (Pt. I) 182.

36. Hdqrs. Department and Army of the Tennessee, Huntsville, Ala., April 18, 1864; 32 O.R. (Pt. III) 401-02.

37. General Orders, No. 20. Hdqrs. Army of the Potomac, April 20, 1864; 33 O.R. 919.

38. General Orders, No. 27. Hdqrs, Army of Northern Virginia, April 5, 1864; 33 O.R. (Pt. I) 1262-64.

39. Id.

40. Id.

41. Priest, John Michael, Nowhere to Run: The Wilderness, May 4th and 5th, 1864 (White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., Shippensburg, PA, 1995) citing, J.F.J. Caldwell, The History of a Brigade of South Carolinians (Philadelphia: King & Baird, Printers, Philadelphia, 1866), p. 126. (Reprint, Continental Book Company, Marietta, Ga., 1951).

42. General Orders, No. 20. Hdqrs. Nineteenth Army Corps and U.S. Forces in W. Louisiana, Franklin, March 7, 1864; 34 O.R. (Pt. II) 521.

43. General Orders, No. 29. Hdqrs. Dept. of West Virginia, In the Field, near Cedar Creek, May 22, 1864; 37 O.R. (Pt. I) 517-18.

44. General Orders, No. -. Headquarters, Valley District, June 27, 1864. 37 O.R. (Pt. I) 768.

45. Id.

46. General Orders, No. 5. Headquarters Department and Army of the Tennessee, Beaufort, S.C., January 25, 1865; O.R. 47 (Pt. II) 127-28.

47. Paragraph 122, US Reg's, page 23.

48. Such a residence is described by Corporal Sam'l Storrow of the 44th Mass. Inf. in a letter written to his parents from camp in North Carolina on 17 March 1863:

I wish you could see us here in our camp of shelter tents. These are made in three pieces about 5 feet square, of stout drilling, one of which each man carries rolled up with woolen blanket in his rubber one. Two of them are buttoned together and raised upon two poles 4 feet long for the body of the tent; the third buttons on behind like a sort of a hood. The poles are secured by two cords which accompany the tents. Thus you have a tent which accommodates three brothers, who must literally be in arms when they are all within.

Wiley and Milhollen, They Who Fought Here (Bonanza, 1959), p. 84.

49. "...an excellent shelter for six soldiers is made as follows:-Three tent-sticks are fixed into the ground, whose tops are notched; a light cord is then passed round their tops, and fastened into the ground with a peg at each end; (Fig. 88.) Two sheets, A and B, are buttoned together and thrown over the cord, and then two other sheets, C and D; and C is buttoned to A, and D to B. Lastly, another sheet is thrown over- each of the slanting cords, the one buttoned to A and B, and the other to C and D; (Fig. 89.) The sides of the tent are of course pegged to the ground." Scott, Military Dictionary, page 136 (Camps).

50. 4 Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 475.

"Tents (says Napoleon) are not wholesome. It is better for the soldier to bivouac, because he can sleep with his feet towards the fire, and he may shelter himself from the wind by means of sheds, bowers, &c."

Scott's - camps - p 132

"Tents made of white stuff are prejudicial to the eyesight in summer, and should be therefore discarded." Same, p. 134